Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.He passed away on July 12, 1999.

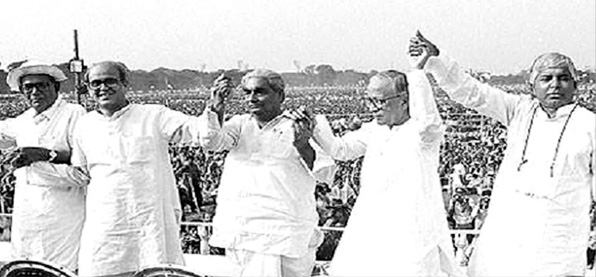

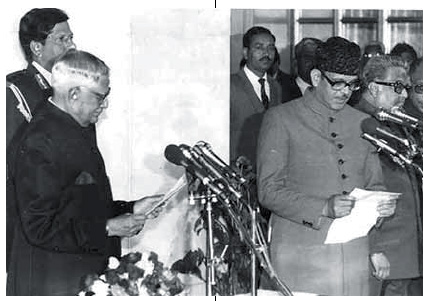

VISHWANATH Pratap Singh started his term as the country’s Prime Minister with a splendid example of ‘value-based’ politics. The newly elected MPs of the Janata Dal, a total of 143 in a Lok Sabha of 543 seats, had gathered to elect their leader and the seventh Prime Minister of India. VP Singh who had spearheaded the onslaught against Rajiv Gandhi, with Bofors as his lethal weapon, was generally considered the ‘natural leader’ of the new party, but he had a rival who was set on taking the crown: Chandra Shekhar. The meeting started with VP Singh proposing the name of Devi Lal for leadership, and Chandra Shekhar at once seconded it. Normally this would have created a lot of sound and fury, because most of the Janata Dal MPs expected VP Singh to be the leader. If there was not even a murmur at this turnabout, it was because Singh’s new friend, Arun Nehru had quietly briefed the MPs about the ‘drama’ they would stage. No sooner had Chandra Shekhar seconded his name, Devi Lal got up and said he was overwhelmed by the honour, but as the elder leader he was proposing the name of VP Singh as the leader. Before Chandra Shekhar could even understand what was happening, Ajit Singh got up and seconded the Tau’s proposal. Shekhar was left high and dry. It was an act of deceit and mendacity, the like of which the Central Hall of Parliament had never seen before.

Deceit and mendacity were the stock-in-trade of both VP Singh and Devi Lal whom he made his deputy. Both of them wore masks of self-effacement; VP far more convincingly than his colleague from Haryana. “I will never again accept any other post in my life” had been Singh’s constant refrain after he resigned from the Rajiv Government. Asked why he would not accept any post, he said, “It is not laying down arms but a change in lifestyle.” “I do not fit in the current situation.” About his future he said, “I think I will only read and write.”

He had laughed off any talk of his wanting to become the Prime Minister by saying that if did become the PM it would be a “national disaster”. Self-disparagement is often taken as a sign of modesty and humility but as it turned out in this case, VP Singh had been prophetic. In 11 months as the Prime Minister, he left the country torn and divided as never before.

The circumstances in which VP Singh resigned from the Rajiv government had suggested an imminent revolt in the ruling party. He was still calling Rajiv Gandhi his leader whom he would never desert. He had scoffed at the “talk of dissidence in the party” and said it was “just in the papers”. Even after he formed his Jan Morcha, Singh continued to act as though he would never touch the Opposition. “I will never fall into the Opposition’s trap,” he told his aides. He was obviously hoping that the Congress would crack and he would emerge as the alternative to Rajiv Gandhi. He had started going around, addressing meetings in various parts of UP and Bihar, but his speeches were still just abstract lectures. He had refused to address a Kisan Union Rally in Haryana because the organisation had opposed the Congress government. At Gorakhpur, where he was prevented from addressing a kisan rally by the then chief minister, Vir Bahadur Singh, he said, “You cannot throw away a shirt just because it has lost a button.”

After his initial plan of breaking the Congress party failed, VP Singh became more receptive to the overtures of some Opposition leaders who were looking for an anchor ever since their debacle in the 1984 elections. By November end, the Jan Morcha went back on its announced policy and joined an alliance with the Janata Party, the Lok Dal (A) and the Congress (S).

VP Singh’s government was truly unique. It was the first and only government in the world which was supported by both the Left and the Right. VP Singh had returned to the early days of his revolt against Rajiv Gandhi, when he had marched out, sometimes going left and sometimes right. The first to lap him up were the ayatollahs of Hindu revivalism. In Varanasi, they anointed him as Rajarshi. It was a title introduced long back by Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya as the highest honour of the Sanatana Dharma. A bit of the glory was washed when it transpired that the Kashi Vidvat Parishad had been ‘hijacked’ by some unauthorised people who conferred the title on VP Singh.

VP Singh’s government was truly unique. It was the first and only government in the world which was supported by both the Left and the Right. VP Singh had returned to the early days of his revolt against Rajiv Gandhi, when he had marched out, sometimes going left and sometimes right. The first to lap him up were the ayatollahs of Hindu revivalism. In Varanasi, they anointed him as Rajarshi. It was a title introduced long back by Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya as the highest honour of the Sanatana Dharma. A bit of the glory was washed when it transpired that the Kashi Vidvat Parishad had been ‘hijacked’ by some unauthorised people who conferred the title on VP Singh.

Fake or real, an obcurantist organisation had given the first push to VP Singh’s caravan. The swift bunch-up of the Hindu forces around VP Singh was not entirely of his own making. It had happened before to Jayaprakash Narayan when he began his movement in the mid-1970s. Throughout the JP movement in Bihar and Gujarat and subsequently during the formation of the Janata Party, the elections of March 1977, and the making of the Morarji Government, it was the Jan Sangh, with the RSS behind it, which played the most crucial role. The merger of parties had turned out to be enormously fruitful for the Jan Sangh, for it could not have dreamt of winning a 100 seats in the Lok Sabha on its own. JP had done for them what all their Gurus put together never could.

But the dream collapsed too soon. In its new incarnation as the Bharatiya Janata Party, the organisation tried hard to become another umbrella party like the Congress but in the process it even lost its basic appeal. The slide had become a rout in 1985: the BJP got just two seats in the Lok Sabha, and all its stalwarts were defeated. It was time to look around for a new prop, and here came the new ‘Messiah’, cleaner than Mr. Clean. They wasted no time in rallying round him, and even found a slogan for VP Singh: Raja nahi fakir hai, Bharat ki taqdeer hai! This indeed was a case of history repeating itself, this time as a farce!

JAYAPRAKASH Narayan had also embraced the Jan Sangh and the RSS, but there was a world of difference between him and the new ‘Messiah’. JP had known too well what he would be up against. An important reason for JP’s moral stature was that his disinterest in positions of power was not a mere pose. He had not fought Indira Gandhi to become the Prime Minister. It was the opposite with VP Singh. The more he repeated that he would never again take a post in the government, the less he was believed. In spite of all his renunuciatory poses, it was apparent that he was seeking power. Within three months of saying he would not take any post, he was the President of the Janata Dal, Convener of the National Front and the leader of the Front’s parliamentary party, and then the Prime Minister of India.

The RSS and the BJP were merely ‘pushing his car’. Having got the initial push, his ever-active mind was working on another track. But he soon turned coy and diffident. Perhaps the calculator inside him gave a warning signal: This isn’t the right way to the throne. He knew that the rightist could take him thus far and no further. What he needed to achieve his goal was a socialist, pro- people image, and if a Raja could not declare himself a leftist, he could well embrace the leftists as his ‘natural allies’. VP set out to carve himself in the Nehruvian mould, and he even had a Nehru of sorts to help him out. Then began his alliance with the Communists who were themselves not averse to making a possible stepping stone out of the Raja. Even so, he never allowed a break in his links with the rightists and refused to succumb to pressures of the left.

One of his principal aides right from the start was Arif Mohammed Khan who had left Rajiv Gandhi solely as a protest against policies meant to appease Muslim fundamentalists, and now the same elements whom Arif had fought were being embraced by his new-found leader, VP Singh. It was only natural for Arif to take umbrage.

All-round inconsistency has been the hallmark of Rajrishi VP Singh. He knew that to get to his goal he would have to change his train. Just a day before the veteran Marxist and chief minister of West Bengal, Jyoti Basu, was scheduled to reach Delhi, VP Singh declared that his “natural allies” were the left parties. He had declared he would not have any truck with communal forces, which at once raised the question whether he thought the RSS and the BJP constituted such forces. That he would reply to. “There is no use calling each other names,” he would say at press conferences.

THE Raja suffered no pangs of conscience playing this double role. Conscience for him was something that rose or slept according to the demands of a political situation. His refrain was that “anyone from a convict to a temple priest is welcome to join me, if he is willing to fight for the issues involved.” And what were the issues? Not communalism, not the return of feudal barbarism or mediaeval obscurantism, not the anti-poor economic policies that he had himself piloted. None of these was an issue as far as he was concerned at that time. His only issue was corruption, and this he was going to fight shoulder to shoulder with VC Shukla, Chimanbhai Patel, Devi Lal and company. How long could he go on fooling the right and the left with what HN Bahuguna had described as his “Mona Lisa stance”?

VP Singh, I wrote in an earlier book, was at his communal best (or should I have said ‘secular best’?) during his own by-election in Allahabad. He had shut up his own aide, Arif Mohammed Khan in ‘purdah’ because he had become a persona non grata with the Muslims after his role in the Shah Bano case, and asked Syed Shahabuddin to campaign for him. “Please come eight or ten days before the polls,” he had urged Shahabuddin. But then Singh’s RSS friends had persuaded him to keep Shahabuddin out of the campaign, and so when Shahabuddin arrived in Allahabad, he was not too welcome. All the same, he went to some Muslim areas and did his best to mobilise support for VP Singh. After his victory, Singh sent him a telegram to thank him. Arif Mohammed Khan was on the warpath. He threatened to expose the ‘double-faced Raja’. He had said, “VP Singh has won Allahabad and lost India.”

Hours after VP Singh was sworn in as the Prime Minister, he was confronted with his first major crisis. Rubaiya Sayeed, the 23-year-old daughter of Mufti Mohammed Sayeed whom he had made his Home Minister, was kidnapped by a group of militants belonging to the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front. They demanded the release of five of their colleagues. Six days later she was released in exchange for five militants.

This gave Rajiv Gandhi, now the leader of the Opposition, with 197 MPs behind him, his first chance to attack his former Finance Minister. He called it a weak and inept government, and accused Sayeed, who had been a favourite of the Gandhis until not very long back, of having links with the terrorists. The kidnapping was all a put-up show, he said, only for the purpose of helping the terrorists. Srinagar was under curfew; Hindus families were running away to Jammu leaving their hearths and homes behind. “There is a civil war going on in Kashmir,” said former Congress minister and Gandhi loyalist Makhanlal Fotedar, “and the Prime Minister does not know how to face it. The government has compromised national security for the Home Minister’s daughter and now terrorists in Punjab as well as in Kashmir are raising more demands because they feel the government is weak.”

VP Singh yielded to pressures from the Bharatiya Janata Party and despatched Jagmohan to Srinagar as governor. His brief was to deal with the situation with an iron hand. On January 19, Jagmohan took over. At midnight, there were massive raids in downtown Habbakadal. About 400 Kashmiris, mostly youth, were dragged out of their houses in a combing operation. Next day over 25,000 people defied curfew at Chhanpora and Natipora, and machine guns were used to disperse the crowd at Gowkadal. At least 60 bodies were loaded onto trucks and taken to the police headquarters. Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah resigned in protest against the appointment of Jagmohan, and the assembly was dissolved. Farooq left for England and it took him very long to regain some credibility in the Valley.

After VP Singh became the Prime Minister, George Fernandes had boasted that now that Rajiv Gandhi was gone, the problems of Kashmir would be solved ‘automatically’. The boast now sounded like a joke. With the Valley going out of hand, Singh had appointed a Kashmir Affairs Committee and made Fernandes the minister in charge of state. Confusion became worse confounded. There was already Arun Nehru who thought he was a specialist on the state, and now there was another minister flying in and out of the Valley every other day, holding talks with militants and passing all kinds of orders, raising the hackles of the Home Minister in Delhi and the governor in Srinagar. Fernandes and Mufti Mohammed Sayeed were often at loggerheads. The police firing on the funeral procession of a prominent religious and political leader, Mirwaiz Farooq, had led to heavy casualties. Singh recalled Jagmohan and appointed a former chief of the RAW as the governor. As a compensation, Jagmohan was given a berth in the Rajya Sabha, a step that came in for severe criticism. “Explaining this, VP Singh points out that the advice was given by official BG Deshmukh who was of the view that Jagmohan should be neutralised, and not allowed to become a BJP ‘martyr’. The approach, VP feels, worked.”

THE Janata Dal was a bizarre experiment which lent itself to much ridicule and banter, at which Rajiv Gandhi’s Boswell, Mani Shankar Aiyar excelled. The real divide, argued Aiyar, was over the conception of the identity of our nationhood: “do we want a diverse but composite, multi-religious, multi-cultural flowering of India — or do we want Hindutva? The destiny of India turns on that question.” VP Singh had won the elections chanting the Bofors mantra, but it became one of his biggest anxieties to prove what he had been saying from city to city. He and his men were leaking stories by the reams on the scandals of the Rajiv Raj, but everyone was asking for the conclusive evidence he had been talking about all through his campaign. VP Singh told Parliament that “we well do everything to get the names and come to the truth.” The CBI had been asked to “pursue the case vigorously”, “the government has approached the Swedish governments to make available the complete report of the National Audit Bureau…” The same old bromides that the people had heard even in Rajiv Gandhi’s time. Everything but the proof. “The investigators,” commented a journalist tired of following the same story for months, “were more buffoons than villains; their stories owed more to cook-ups than conspiracies, and their failures stemmed from simple ineptitude. More than anything else, they committed one cardinal sin: they suspended the rules of logic and evidence and believed their own propaganda.”

The one notable feature of VP Singh’s 11 months in office was the phenomenal rise of Devi Lal and Sons. In 1989, when Tau became the Deputy Prime Minister, he handed over the reins of the state to his son Om Prakash Chautala. When the value-based Prime Minister, VP Singh, showed a little unhappiness about the later activities of Chautala, Devi Lal told him: “You should not be talking about political morality. You became the Prime Minister only because I told a lie.”

In order to win a lost election, Chautala had teamed up with his son Abhay Singh to terrorise the constituency, Meham. The police turned a blind eye. There was a virtual bloodbath on election day. Chautala refused to step down. At a huge Boat Club rally on his 75th birthday, Devi Lal proclaimed himself as the Tau of the nation. “But it rapidly became apparent that the nation comprised his four sons, their wives, grandsons, and some kith and kin,” said a commentator.

When Meham became a major issue, Devi Lal resigned, creating the first major political crisis for VP Singh. The Prime Minister’s first instinct, he told his aides, was to accept the resignation. “I should have, I should learn not to ignore my first instinct, and if I had had any sense I would have accepted it.”

The Prime Minister perhaps realised that Devi Lai would be a far greater threat outside the government than within it. He joined those clamouring for his return, and wrote a remorseful letter, declining to accept the resignation….” You have been one of the main architects in forming the Janata Dal and have greatly contributed to its success in the elections.”

Sometime later, the five-member committee of the Janata Dal which had inquired into the Meham incident recommended that Chautala should step down from the leadership in Haryana. Finally, after a great deal of flip-flop, the Prime Minister thought it was time to act and the party directed Chautala to resign. Fifty days after his removal, Chautala was reinstated as Chief Minister. Nobody doubted that this was part of a deal struck between the Prime Minister and Devi Lal.

The Prime Minister’s problems started some days later when Arun Nehru returned from a foreign trip and got into the act. He decided that he would resign. Nehru accused VP Singh of betraying the “hopes that we raised among the people in the course of the struggle” and “dealing a stinging blow to the image and credibility of the party and the government.” There was panic in the Janata Dal. “I am not claiming that I am the only moral person in this government,” Arif Mohammed Khan told the press. “My point is different. When there was violence at Meham, the Prime Minister told Parliament that the cabinet would take a decision. The cabinet decided to ask Chautala to resign. Now how can you bring the same man back in defiance of decisions reached by the cabinet and the party high command?” Devi Lal was livid. He could not stand these “riff-raff talking about principles”, he said. In a conversation with Arun Shourie, then editor of the Indian Express, he had even used four-letter words to describe Arun Nehru.

VP Singh was in a bind. The only way to survive, he decided, was to mount a ‘counter-attack’. He used his ultimate weapon: his own resignation. It was an old ploy that he had used with great effect in the past. He sat down and wrote: “The rationale of my being in the office of the Prime Minister was the trust of the people, of the members of the National Front and of the supporting parties. The developments during the last two days have shown that I have lost that trust. The rationale of my continuing in office is no longer there. Bowing to the general sentiments I wish to step down from the prime ministership…”

The purpose of the letter was clear. Had VP Singh really wanted to quit, he would have sent it to the President of India. Instead, he sent it to the president of the Janata Dal, his explanation being that if he had sent the resignation directly to the Rashtrapati Bhawan it would have paved the way for the return of the Congress. All that VP Singh wanted was to give a new turn to the crisis. Party president Bommai rushed around from leader to leader, seeking their advice and consent. Reject the resignation, everyone said. Suddenly neither Arun Nehru nor he was the issue: Devi Lal was. Six ministers of state and deputy ministers quit in the space of a few hours….All gave the same reason: Chautala should not have been brought back.

“I don’t know about the rest of you,” Chandra Shekhar said during a meeting to discuss the VP Singh’s resignation, “but I am sick of these two men (VP Singh and Devi Lal) and their fights. They conspired to turn the leadership elections into a fraud and elected a Prime Minister through conspiracy. One has made his son a chief minister, the other has made his damaad (son-in-law) a Rajya Sabha MP…How long can this go on? …Then turning to the Prime Minister, he asked: “Now, you tell me, what was the deal? What had you and Devi Lal agreed on?” VP Singh kept quiet. He kept looking at the table.

The crisis deepened. More ministers resigned, and the government was at a standstill. Finally, Devi Lal made his conditions known: The new chief minister would have to be his man; Om Prakash Chautala would continue as the general secretary of the Janata Dal; the resignations of Arun Nehru and Arif Mohammed Khan should be accepted. There were many more demands.

After four days the whirlwind settled, but it was the beginning of the end of the Raja’s government. Devi Lal was now determined to bring the whole edifice down. Within days he plunged the party into a fresh crisis by levelling charges of corruption against Arun Nehru and Arif Mohammed Khan. When the Prime Minister insisted that he substantiate these allegations, Devi Lal sent him a forged letter reportedly written by VP Singh to the President of India in 1987 accusing Arun Nehru of being involved in the Bofors deal. VP decided that the contradictions had gone beyond his control. With the backing of the national party, VP Singh wrote to the President on the midnight of August 1, 1990, recommending the dismissal of the Deputy Prime Minister, Devi Lal.

Devi Lal had already announced his great offensive: a kisan rally on August 7. But the Raja had a far more potent weapon up his sleeve. Just two days before Devi Lai’s planned rally, the Prime Minister made a suo moto statement in Parliament. A “momentous decision of social justice” he called it. “The percentage of reservation for the socially and educationally backward classes will be 27 per cent, and this reservation will be application to services under the government of India and public undertakings…”

THE acceptance of the Mandal Commission report, which had been gathering dust in the entrails of the Home Ministry for years, took the country by storm. Violent reaction gripped some of the major cities in north India. Students went on rampage, burning buses, attacking government property. Some were killed in police firing in Delhi, Gorakpur, Varanasi, Kanpur, Madhubani and Dhanbad. In Jaipur, the Army was called out. At first students burnt their degrees, then some got down to burning themselves. Conscious of the genie he had unleashed, the Prime Minister declared from the ramparts of the Red Fort: “If power in the hands of the rulers could be compared to a sword, it shall act against the exploiters.” It was VP Singh in his new political incarnation — the Messiah of the Backwards!

When Lal Krishna Advani went to visit one of the boys who had tried to immolate himself, he was heckled and attacked by Delhi University students. He could see that in one stroke VP Singh had changed the entire socio-political dynamics of the country. It was high time that his party came up with something to counter the VP Singh card. Rath Yatra was the answer. Mandir against Mandal. The BJP mind had its limitations.

After Advani launched his yatra, the Prime Minister spoke to Atal Behari Vajpayee and asked him why they were doing it. Vajpayee said: “Aap ne Mandal kiya to hum Kamandal kiye.” Vajpayee himself had scoffed at the Rath Yatra, but it was beyond him to stop it. The BJP was convinced that in playing the Mandal card, the Raja had declared his election manifesto. They had to answer it with their own manifesto: the ‘liberation’ of Ram Janmabhoomi.

When VP Singh played his brilliant card, he could hardly have visualised that he would have to pay for it with his chair, though he later claimed he did: “There is a certain price tag to everything, and you have to be prepared to pay the price. You cannot get the thing and then regret paying the price…maal leyaao to daam dena parega. Mandal implent kiya to uska daam bhi dena para.”

“Through Mandal, I knew we were going to bring in changes in the basic nature of power. I was putting my hand on the real structure of power. I knew I was not giving jobs, Mandal is not an employment scheme, but I was seeking to place people in the instrument of power through the use of governmental power… History is not changed without an element of ruthlessness and once you have set out on this course to make real change permanent, you have to have an element of ruthlessness…I knew he decision would trigger off new realignments. And I was also clear about my fate. I had visualised it.”

The Prime Minister had indulged in all kinds of antics to save his government. He had first tried for a compromise acceptable to both sides, and convened an all-party meeting, but the BJP refused to attend. The party’s national executive warned the government that if the Rath Yatra was disrupted or attempts were made to prevent the construction of the Ram temple, it would withdraw support to the government. Caught in a cleft stick, the VP Singh government issued an ordinance acquiring the entire disputed area in Ayodhya, then withdrew it two days later when Muslims of the area protested that the ordinance would affect the title suits they were fighting in various courts. After he had run out of all his cards, VP Singh declared on television that he was going to ‘stand up for secularism, regardless of the cost to his political career.’ The Advani Rath was then in Bihar, and Chief Minister Laloo Prasad Yadav was not going to let such an opportunity slip through his fingers. He stopped the Rath at Samastipur and arrested Advani. The BJP withdrew its support the same day — October 23, 1990.

VP Singh went to Rashtrapati Bhawan, not to submit his resignation but to convince R Venkataraman that he could still manage the contradictions. All he needed was a little time. The President set November 7 for the 11-month old government to prove its majority in the Lok Sabha.

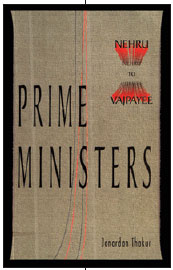

Excerpted from Prime Ministers: Nehru to Vajpayee by Janardan Thakur, Eeshwar Prakashan, New Delhi