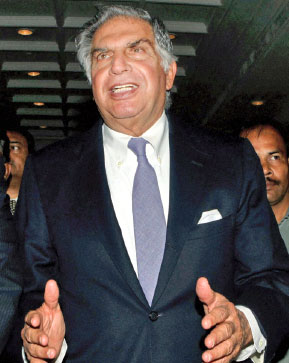

ROME wasn’t built in months. Nor was it destroyed in months. The same is the case with the spat between Ratan Tata, interim Chairman, Tata Group, and Cyrus Mistry, former Chairman. The story starts, ironically, when Ratan decided to search for his successor. The year: 2010. The five members of the selection committee included Ratan’s loyalists-NA Soonawala, RK Krishna Kumar, the UK-based Lord Bhattacharya, Shrin Bharucha, and, of course, Cyrus, whose family owns 18 per cent in Tata Sons, the group’s holding company.

Cut to November 23, 2011. After 18 meetings in search of a professional outsider to carry on the almost 150-year-old Tata legacy, the committee selected Cyrus, who was already an insider as Tata Sons’ director. He was actually an insider-outsider, possibly the worst combination for a successor of a $100-billion business empire. An outsider invariably comes prepared; he knows that as a professional and non-owner of a family-owned group, he can go thus far, and no more.

An insider is invariably a loyalist and follower, who will look up to the owner; even better, he may be a part-owner himself and, hence, is part of the family.

Both an insider and outsider can turn rogue. They can develop or nurture their own ambitions, try to usurp the group, or develop an urge to leave a new legacy behind. However, the chances of these happening with an insider-outsider are larger. Being an insider, he will feel that he owns the empire. Being an outsider, he will wish to change things around and attempt to transform the group to prepare it for the future. An insider-outsider has the best of both worlds, which can quickly shift to the worst of both. This is what happened to Cyrus.

For an owner too, an insider-outsider is a tricky person to deal with. The owner is always scared that the latter, as an insider, will try to take over the businesses-Ratan did claim that Cyrus wanted to control the 100-odd operating arms of the group. He is also nervous that as an outsider, the successor will want to undo past decisions-Cyrus did wish to sell the European steel business and wind down the operations of the Nano car, both of which were Ratan’s dream projects.

So, the story began on a wrong note, a sour one, albeit in a subconscious manner. In a Freudian manner, both Ratan and Cyrus repressed these negatives. They both felt that since they had worked together for years, they understood each other and the bonhomie would continue forever. They should have read more of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung to understand how human psychology works, and how it changes rapidly when one is given powers, and the other has to give up his erstwhile powers. We all know that power corrupts-in fact, in both ways, i.e. additional powers and subtraction of powers.

TO be fair to Ratan, he had a clue about the workings of the mind of an insider-outsider. So, as an owner, he designed things to retain control over his empire. Cyrus worked with Ratan for a year, and only took over formally in December 2012. But during this period, Ratan had already impressed upon the newcomer that he would not have full control; his powers would be restricted by the owner. The idea was to protect the ownership of the sprawling empire.

The ball was put in play even before the new successor took over in December 2012. But, before that, it is imperative to understand who owns Tata Sons. Seven Tata Trusts together own almost two-thirds of the shares of Tata Sons, the group’s holding company-the shares are “held by (seven) philanthropic trust endowed by members of the Tata family,” says the Tata Group website. It adds, “The largest of these trusts are Sir Dorabji Trust (stake: almost 28 per cent) and the Sir Ratan Tata Trust (over 23.5 per cent), which were created by the families of the sons of Jamsetji Tata, the Founder.” Ratan headed these two trusts.

In 2012, Tata Sons’ Articles of Association was changed to protect Ratan’s holdings and wealth. Any removal or appointment of chairman now required mandatory approval by all the directors that were installed by the Tata Trusts. In addition, the Trusts had the right to appoint a third of the board directors. This was done with Cyrus’ okay. Negotiations were on for further changes. In 2014, a new arrangement was in place between the owner and the successor.

In 2012, Tata Sons’ Articles of Association was changed to protect Ratan’s holdings and wealth. Any removal or appointment of chairman now required mandatory approval by all the directors that were installed by the Tata Trusts. In addition, the Trusts had the right to appoint a third of the board directors. This was done with Cyrus’ okay. Negotiations were on for further changes. In 2014, a new arrangement was in place between the owner and the successor.

UNDER the new deal, the Tata Trusts got more powers. Their directors virtually had veto powers over the group’s strategic decisions-mergers, takeovers, investments and fund-raising. The majority of the Trusts’ nominees, two out of three, had to approve such decisions, even if the board’s majority had done it. They also had veto powers over the annual and five-year business plans. The owner made sure that the successor couldn’t take over his businesses.

Still, as a professional, Ratan gave Cyrus enough freedom to take day-to-day and tactical decisions. In fact, in 2013, before the above agreement, the latter formed a committee to guide the group’s future. Apart from himself, who chaired it, it comprised five members, most of whom were his handpicked men. The Group Executive Council, as it was called, included Madhu Kannan, the former CEO of the Bombay Stock Exchange whose name will feature later in this saga. It was meant to provide strategic and operational support to Cyrus.

The new die was set. The contours of the new relationship were established. And both the owner and the successor felt that they would live happily thereafter. Neither of them gave a damn about egos, shifting loyalties, baggage, legacy, trust, power, jealousy, and ambitions. But humans, even if they are billionaires and chairmen of powerful empires, live in an uncertain world where things change imperceptibly, and wreck havoc.

Wings # 1: Dramatis directors

Wings # 1: Dramatis directors

One of the first signs were witnessed in 2013, when the Tata Trusts appointed new directors in Tata Sons. These included Nitin Nohria, Dean, Harvard Business School, and Vijay Singh, the former Defence Secretary, both of whom became hugely controversial after Cyrus’ dismissal. Cyrus had problems with them. Since both were Ratan’s confidantes, they had Ratan’s ears and advised him on most deals. This irked the new chairman. Cyrus wanted Ratan to deal with him, rather than through what the owner heard from Nohria and Singh.

It was a classic insider-outsider mindset, who thought he was an insider and, thus, should have the owner’s ears. Cyrus thought that Singh was ‘un-Tata-like’, and wrongly advised Ratan. He revealed his feelings after his ouster. In a statement, he said that Singh, as the Defence Secretary, was involved in the scam-tainted AugustaWestland chopper deal, which was signed by the previous UPA-2 regime, and cancelled by the present government. It was alleged that bribes were paid in the deal. Singh retorted that the deal was signed a year after he left, as the Defence Secretary, although the negotiations began during his tenure.

Cyrus viewed Nohria as a thorn too. In his worldview, the Harvard Dean became the non-executive director only because of his friendship with Ratan. Years ago, in 2010, Ratan donated $50 million to the School, which was its largest gift from an international donor. Therein lay, according to Cyrus, the links between the former chairman and owner, and the new director. Yet again, it was a classic outsider’s view of an insider-outsider; it wasn’t a professional appointment. It is a different case that Cyrus was wrong on both counts; his view was blurred as both Nohria and Singh enjoyed excellent credentials.

An insider-outsider is a tricky person to deal with. The owner is always scared that the latter, as an insider, will try to take over the businesses, and as an outsider, will want to undo past decisions—Cyrus did wish to sell the European steel business and wind down Nano’s operations

Wings # 2: Take-off troubles

More tremors happened in 2014, when the Tata Group re-entered the aviation sector through Air Asia. This was yet another project that Ratan desired for several years; his earlier efforts had failed. Here, there was a family legacy. Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata, JRD or Jeb, was the uncrowned king of the group. For over five decades, between 1938 and 1991, he had taken it to towering heights, before he relinquished the reins to Ratan. Aviation was his passion.

ON the IATA website, a blog reads, “His hero was the French piloting ace Louis Bleriot, the first man to cross the English Channel by air. Bleriot lived near the Tata’s French county home and once allowed a co-pilot to give the 15-year-old JRD a ride. From that moment on, JRD was determined to fly.” And set up an airline, which he did in 1932. Tata Airlines was the first Indian commercial carrier; in 1946, it became Air India. After Independence, the airline was nationalised, although JRD remained its head until 1978.

Ratan wanted to relive JRD’s high-flying dream. For obvious reasons! Moreover, as an owner, he was a risk-taker to an extent. He had a 20-,30-,40-year vision in his mind. He wasn’t affected by today’s facts-the aviation sector was in trouble, most airlines were in the red, especially the low-fare carriers, and it was difficult to raise funds. He was looking at how, like Jeb, he will revolutionise the sector over the next decade or so; how he will bring world-class management and operational practices to India; how he will introduce renowned airlines, Air Asia, to the Indian passengers. Air Asia, incidentally, is the first foreign airline to set up a subsidiary (49 per cent) in the country. Which one should be proud of!

However, in this case, Cyrus thought like an outsider, a professional who wished to show instant results. Immediate performance generally, and especially in the case of a new CEO or chairman, implies cutting expenses, selling loss-making assets, and exiting seemingly-less profitable sectors. Globally, this mindset became famous, and quite common, in contemporary times during the 1980s. As a new wave of takeovers and mergers, especially leveraged buyouts (LBOs), became fashionable, the only way the new owners could reduce the huge debt required to buy the assets, was to sell part of the existing assets, and tighten belts. This is exactly what Cyrus had in his mind, but he needed to act and think like an owner to take such crucial and emotive decisions.

LOGICALLY, since 2013, he opposed or cribbed about the entry into the aviation sector. But there was a problem-he was neither a full-fledged insider, nor a complete outsider; he forgot that he was an insider-outsider and, hence, he had a lot of freedom, but also many strategic shackles. He simply couldn’t wish away the aviation partnership. Air Asia India was here to stay.

Wings # 3: Parsi parsimony

For decades, in some cases a century, the Indian Parsi community, especially the families based in Mumbai (or Bombay), earned huge sums from the Tata Group. Over the years, they had invested, reinvested and re-reinvested their earnings to buy the shares of the various companies, especially the blue chips like Tata Motor, Tata Steel and Tata Consultancy. Over the years, they had preserved the shares, not sold them, as they witnessed a huge rise in their paper profits. In addition, they earned huge dividends from these companies. Ever since Cyrus took over, they were worried, even angry and disturbed.

The reason: the new chairman’s thinking like an outsider. As explained earlier, Cyrus wanted to show his capabilities instantly. Like the two-minute Maggie noodles, he hoped to prove within months, at least years, that he could turnaround the fortunes of the group companies. He would be better than Ratan; even better, he would make people forget Ratan’s achievements sooner than anyone expected. His instant philosophy: cut down the shareholders’ dividends of companies that weren’t faring well. It piqued the Parsis, especially those who thrived on returns from their investments.

Inevitably, the entry of a second Parsi in the Tata Group, and exit of the more famous one, created rifts between the rich people within the community. Since the first half of this century, the Mumbai-based Parsis witnessed the loosening of their stranglehold over business, wealth and power to the Marwari and other trading communities. Hence, they generally stuck together, helped each other, and protected themselves. This is evident from the earlier almost-family-like links between the Tata and Mistry, Ratan and Nusli Wadia, the business fighter who owns the Bombay Dyeing Group, and Ratan and Mehli.

In 1997, the Indian Express published the transcripts from what were called the Wadia Tapes or Tata Tapes. These related to conversations that Wadia had with politicians, political middlemen, businesspersons, and Tata over what came to be known as the Tata Tea Terror controversy. In that period, like other businesses, Tata Tea, whose operations were in Assam, had issues with the militant organisation, ULFA (United Liberation Front of Assam). It was alleged that the Tata Group had indirectly financed the expenditure of ULFA leaders-like a free hospital where ULFA leaders and members were treated, and foreign trips and stays for the leaders. Ratan apparently knew ULFA’s chief.

THE tapes and their conversations proved Wadia’s proximity to Ratan, and the former was his political trouble-shooter to clean up this mess. The transcripts reveal that the former was the latter’s Man Friday. In addition, Wadia was a director in Tata Sons and a number of other operational entities. In the recent past, and after Cyrus took over, Wadia distanced himself from Ratan, and got closer to the new chairman. The rift in the rich Parsi community had begun. Thus, it wasn’t surprising that when Cyrus was kicked out, Wadia took his side. In the end, Wadia was kicked out of the various Tata firms.

Wadia filed a defamation case against Tata Sons, when he was ousted as an independent director. He claimed that the manner of the removal “caused severe prejudice to the reputation and goodwill” that he enjoyed. In a prescient moment, he correctly predicted that it had “affected his status as an independent director in various other companies and will continue to have a cascading effect” in the Indian and global business circles. It did to an extent; other Tata firms kicked him out too. The fissures within the community increased.

Another fracture among the rich Parsis was actually rifts with the Mistry family. Cyrus has a cousin, Mehli, who is a longtime friend of Ratan. Somehow Cyrus, whose family is in the construction business, had problems with Mehli, who had bagged several dredging, shipping and barge contracts from Tata Power. The then chairman felt that this was because of Ratan-Mehli proximity. Through his lawyer, Mehli told the media that this wasn’t true, and the contracts were valued fairly. But the two Mistrys couldn’t get along; one of them (Cyrus) thought the other ratted against him to Ratan, which was why he lost his chairmanship.Then there were the quakes, which added immensely to the Corporate tsunamis within the Tata Group, and finally drowned Cyrus.

Timeline

October 24… Cyrus Mistry was removed from the post of Tata Sons chairman without any explanation.

October 25… Shapoorji Pallonji & Co kept their action secretive. Tata Group filed appeal in the Supreme Court, Bombay High Court and National Company Law Tribunal to ensure that Mistry doesn’t get an ex-parte order against his sacking.

October 26… Mystry wrote a scornful letter to board members. He elaborated in his letter about difficulties he faced during his tenure. SEBI asked for clarification from Ratan Tata over Mistry’s letter.

October 27… Air India looked into Mistry’s fraudulent transaction’ of `22 crore. Tata Sons responds to the letter, calls Mistry’s claims ‘unsubstantiated’ and ‘malicious’ and that Mistry chaired the Board meet of Tata Global Beverages.

October 28… Mistry denied allegations of Board not consulted over purchase of Welspun Power. Mistry also says he is surprised with reasons that Tata gave for his removal.

October 29… Tata Group’s HR chief NS Rajan resigns from the company.

November 2… Ratan Tata wrote another mail to employees saying that removing Mistry was absolutely necessary for the future of Tata Group.

November 4… Tata Sons appoints S Padmanabhan to oversee HR functions. Mukund Rajan, former executive assistant of Ratan Tata, will be overseeing group operations in US, Singapore, Dubai and China alongwith ethics and sustainability duties.

November 5… Tata Motors defends its `1 lakh Nano car strategy, which Mistry had mentioned in his letter.

November 9… Tata Sons sacks Mistry as Chairman of TCS, replaced by Ishaat Hussain.

November 15… Tata Global Beverages sacks Mistry as Chairman, replaced by Harish Bhat.

November 21… Nusli Wadia, independent director in Tata Steel, Tata Motors and Tata Chemicals, serves defamation notice on Tata Sons’ board.

November 25… Tata Steel removes Mistry as Chairman, appoints independent director OP Bhatt in his place.

December 5… Mistry seeks government’s intervention to ‘remedy and repair breakdown’ in the governance of Trusts managing Tata Sons.

December 13… Mistry removed as TCS director after shareholders vote in EGM.

December 19… Mistry quits as director from boards of key operating Tata companies before scheduled EGMs; describes his sacking from Tata Sons as ‘illegal coup’.

December 20… Mistry moves NCLT against Ratan Tata, Tata Sons and some of its directors.

December 23… Ratan Tata says ‘however painful’ the fight with Mistry may be, but ‘the truth will prevail’.

December 27… Tata Sons slaps legal notice on Mistry for alleged breach of confidentiality.

Quake # 1: Cracks within Bombay Club

IT wasn’t just the Parsis; the breakdown in the relationships between Ratan, Cyrus, Wadia and Mehli devastated the bonhomie that they enjoyed with the larger business community in Mumbai and the rest of India. It was essentially a breakdown of the on-and-off informal business group, dubbed as the Bombay Club. During World War II, and two years before India’s Independence, eight industrialists headed by JRD (who else?) and comprising GD Birla, Sri Ram, Kasturbhai Lalbhai, and Sir Purshottamdas Thakurdas, published the ‘Bombay Plan’. They were the original Bombay Club. The Hindu traders and Parsi businessmen had got together to secure their future.

The Plan presented a series of proposals for the Indian government in the post-Independence era. Although most experts and economists contend that the Club argued for larger State interventions and public investments on State-owned sector, the larger intention was ‘protectionism’ of the Indian-owned industries against the foreigners. This fell under the ‘nationalist’ notions that Indian business was unduly exploited by the British and British-owned firms. Intuitively, the Plan argued ‘for private property’ in a nuanced manner.

Once India glided on the path of economic reforms in 1991, similar fears gripped the domestic business community. In 1993, another group of eight industrialists, comprising Hindus and Parsis, met at Mumbai’s Oberoi Hotel (hence the name, Bombay Club), finalised a note, and handed it over to Manmohan Singh, the Finance Minister. According to media reports, it “welcomed competition in the market but urged the government to take steps to ‘enable them to play their rightful role in the industrial development of the country’.” They were seeking not protectionism, but time to prepare for the inevitable foreign onslaught. According to journalist Sucheta Dalal, who claims to have coined the phrase, Bombay Club, its “agenda really was stalling and slowing (the) reforms.”

Although Ratan was not a member of the second Bombay Club, unlike JRD who was the head of the first, his closest ally, Wadia, was connected to it. It’s unclear whether Wadia attended the Oberoi meeting, but he supported it. Hence, Ratan, without coming out openly, did the same. If this contention is true, then it is clear that the powerful Ambanis-Dhirubhai and his two sons, Mukesh and Anil-who were against Wadia and, hence, Ratan, were not part of the Bombay Club. In fact, the Ambanis had their own privileged and premium club, whose members were die-hard loyalist, who were few in those days.

Now with the Ratan-Wadia feud, and Cyrus-Mehli spat, the final nail has been hammered into the coffin of any form of an informal Bombay Club.

Quake # 2: Loco about DoCoMo

The event that happened sixteen days before Cyrus’ exit, proved to be the ‘tipping point’ or the ‘catalyst’ as far as Ratan was concerned. It confirmed that Cyrus would decimate the carefully-constructed empire; he would devastate every brick in the walls of his operational companies. It verified that his own ownership in Tata Sons, and other companies, and his investments were at risk, thanks to the past decisions taken by Cyrus since he became the chairman.

For years, there were issues between the two partners, Japan’s NTT DoCoMo and Tata Teleservices. After the former decided to exit the venture, it demanded a pre-decided price for the shares it owned under the pre-decided buyback arrangement with the Tatas. However, as similar arrangements existed in the case of other deals involving foreign partners, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) stepped in. Any deals on pre-determined prices were effectively banned. DoCoMo opted for arbitration and won an award for $1.17 billion from the London Commercial Court. However, the change in laws prevented the Tatas from paying it.

TATA Sons maintained that the payment required RBI permission, which was denied. Even after DoCoMo approached the Delhi High Court to impose the arbitration award, Tata Sons placed the entire amount with the court, which showed its intention to pay, but as per the Indian laws. Hassled by what it perceived as Tata Sons’, or rather Cyrus’, deliberate delaying tactics, the Japanese firm threatened to take legal recourse globally to attach Tata Group’s assets abroad. Cyrus argued that this wasn’t possible as the foreign assets belonged to Tata Steel and Tata Motor, and the promoters had minority shares in them. Effectively, the majority stakes in, and the assets of, the companies belonged to the other institutional and individual shareholders.

On October 8, 2016-Cyrus was removed on October 24-DoCoMo dropped a corporate warhead. It filed a case in a court in New York. This effectively put at risk the revenues (its assets are generally human resources) and profits of Tata Consultancy, which earned more than half of its revenues from North America. In addition, Tata Sons owns a majority 74 per cent stake in Tata Consultancy, which paid `11,400 crore (2014-15) and nearly `6,300 crore (2015-16) as dividends to Tata Sons. In both the years, TCS’s dividends comprised 95 per cent and 91 per cent, respectively, of the total annual dividends earned by Tata Sons.

No way would an owner risk such humungous profits for a part-owner.

Quake # 3: Sale of family jewels

As mentioned earlier, being an insider-outsider confused Cyrus. Sometimes, he saw himself as an insider, other times as an outsider. Unfortunately, there were occasions when he behaved like an insider and an outsider while dealing with the same issue. As mentioned earlier, in terms of showing instant results, he was clearly an outsider. As mentioned earlier, one of the key traits of a CEO-in-a-hurry, or chairman-in-a-hurry, is this desire to sell of loss-making or unproductive assets to boost returns and profits percentages. Unfortunately, Cyrus, who played this role on and off, chose the wrong assets to dispose off.

Cyrus fixed his radar on Tata Steel’s global business, and the Nano car project, both of which were the owner’s passionate dreams. These were the two projects which Ratan felt were his real legacies; people would know and remember him for a small car which was the cheapest in the world, and the purchase of a $12-billion Corus Steel in the UK. The first established him as a doer, an implementer, a visionary, an entrepreneur par excellence. The second was his ability to transform the Tata Group as a global MNC, larger than whatever any other Indian had achieved. Indians have bought foreign assets, but none as large and as frequently as he had, especially in the last decade of his chairmanship.

DONNING his hat as a professional, Cyrus felt that the Nano was losing money, and needed to be shut down. It was a wrong project to begin with, for no rhyme or reason other than to set up a milestone-cheapest car. It failed to deliver on what it promised; it failed to lure the two-wheeler owners to shift to a cheap car. Buying an automobile is an aspiration, a desire. And Indian consumer didn’t want to own the cheapest car; her first car purchase had to be a decent model, one that can firmly put her on a middle-class pedestal.

Tata Steel, or rather the expensive Corus Steel, was a millstone around Tata Group’s neck. And it was increasingly bringing it down, especially in terms of debt. In the beginning, Ratan had paid a much higher amount than what it was worth, only because of the owner-former chairman’s ambitious ego. According to a recent article, “When Tata Steel bid for Corus Plc in 2006, it arranged financing with three banks for around $5 billion to $6 billion, said the person, who asked not to be named because the negotiations were private.

As the price rose (Ratan kept on raising the bid price) in a bidding war for the European steelmaker, Tata officials found cheaper funding, but would have to pay a break fee with the original banks of about 80 million pounds ($99 million). Some executives tried to negotiate a cheaper release, but when the matter was brought to the attention of Ratan Tata, he insisted the original contract be honoured, the person said.” Ratan did the same, but only as an owner, during the DoCoMo arbitration.

Cyrus decided to put the global steel assets on the auction block. It was feared that he would wind down Nano. Clearly, no owner would stand for an outsider-insider, his successor, to erode his most-famous legacies. It is easy to understand Ratan’s current emotional state. “Over the last two months, there has been a definite move to damage my personal reputation and the reputation of this great group-the Tata Group. And these days are very lonely because the newspapers are full of attacks, most of them unsubstantiated but nevertheless very painful.”