CHARAN Singh was India’s Prime Minister for one hundred and seventy-one days, but he set a unique record. He sat for less than forty seconds in the Prime Minister’s seat in Parliament.

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.He passed away on July 12, 1999.

He was a man driven by an obsession. He had to become the Prime Minister no matter what the cost or the humiliation, no matter for how long. So desperate was he to get the crown, if only to satisfy some deep craving in his heart or just to prove his soothsayers right, that he forgot all his Gandhian principles, all about means and ends. He swallowed all his pride and prejudices, all his allergies toward Indira Gandhi and Nehru. But having achieved his goal he reverted to his old pride and principles even at the cost of losing the crown he had wangled. All that mattered was that he had worn the crown, never mind if it had turned tinsel.

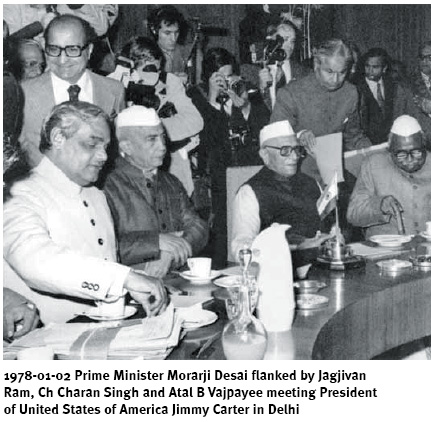

The Morarji government was barely two years old when people started asking: How much longer will this government dance around Indira Gandhi? How much longer will the country live with a gerontocracy that cannot see beyond its nose? How soon will the Janata Party break? Was the country heading for another mid-term elections? Questions came thick and fast, but there was very little by way of answers. Pundits of the Press were full of answers, but history makes political journalists look foolish, and the history of those days had been particularly nasty to the craft. But then politicians were in the same plight; they too could not see the wood for the trees. Politicians were like actors delivering dialogues from different plays of different historical periods. The result was close to bedlam.

Tearing through this medley came the new challenge of Charan Singh. He had displayed his power on Delhi’s Rajpath on December 23, for the second time in two years. Temporarily out of the Morarji Government, he was celebrating his birthday. His followers thundered that they were going to take over the Krishi Bhawan and the Rail Bhawan and all the Bhawans. Behind them lay the debris of a social system which some were still dreaming to perpetuate.

It was almost like a death-wish, but with the disenchantment with the Janata Government so complete and the drive toward the Prime Minister’s chair becoming so strong, Charan Singh was vulnerable to the new overtures from Mrs Gandhi. At 77, Charan Singh had little time left. He had been humiliated by the very party he claimed to have built. “I was hounded out like a dog,” he told reporters the day after he resigned from the Morarji government. With growing dismay, Charan Singh had watched his strength in Parliament being eroded, simply because a Prime Minister had so many loaves and fish to offer. He had started with at least 81 Bharatiya Lok Dal men in the Lok Sabha, and now he expected no more than 50 to go out with him if he left the Janata Party.

Charan Singh looked at all other politicians from a high moral perch, and they all looked very small and mean to him. He thought Jagjivan Ram a man without any sense of morality. In private he would often ask his close aides, “Woh chamar ka kya khabar (What news of that cobbler?).”

Charan Singh looked at all other politicians from a high moral perch, and they all looked very small and mean to him. He thought Jagjivan Ram a man without any sense of morality. In private he would often ask his close aides, “Woh chamar ka kya khabar (What news of that cobbler?).”

He was desperate to throw Morarji out. His luck turned when he met Kalyanam, an assistant to P.N. Balasubramaniam. From him he learnt about all sorts of shady deals between P.N. Balasubramaniam and Kanti Desai. The businessman was a frequent visitor to the Prime Minister’s residence, and Sanjay had been keeping a close watch on him. He also knew of the deals between Bala and Kanti, but he did not want to expose Kanti through the information he got from Bala because he was a friend of the Anands, his in-laws. Besides, Sanjay’s main objective was not just to topple Morarji government, but to destroy the Janata Party itself.

Finally installed on the throne, Charan started acting high and mighty with the very people who had put him there: the Gandhis. He spurned suggestions that he should personally go to Mrs Gandhi and thank her for her support. “Why should I?” he said, “The people will think I have surrendered to her. It will not be good for my image.”

Within hours of Charan Singh becoming the Prime Minister, even his ‘Hanuman’, Raj Narain, was acting brave. At a Ramlila Maidan rally, he publicly denounced Sanjay Gandhi. His friend, Maniram Bagri, described Mrs Indira Gandhi as a “rat” whom they would soon crush.

Raj Narain only meant it to be his public face. On returning to his residence, he immediately telephoned Sanjay Gandhi and begged to be forgiven for the “slip” he had made at the meeting.

But there were several other irritants, which were making the Gandhis angry. The list of Congress ministers to be included in the Charan Singh cabinet had ‘enemies’ of the Indira Palace and some ‘turncoats’. The list had caused a controversy even in the Congress (S) itself. Mrs Gandhi’s emissaries made it very plain to Charan Singh that his days were numbered. Ironically, Charan Singh did not even see that he himself was now surrounded by some of the same people he had earlier described as a “pack of impotent people”. Now that he was himself heading the ‘pack’, all of them had become ‘potent’. Nobody could have missed the irony of the situation, the strange twist that politics had taken. The same Raj Narain, who had vanquished Indira Gandhi legally and electorally and brought down her edifice was now hand in-glove with Sanjay Gandhi, the enfant terrible of the Emergency. Charan Singh, who had nothing but contempt for the Nehru dynasty was now at the mercy of the ‘wicked Cleopatra’, surviving on the sufferance of Sanjay Gandhi. Indeed, the mother and son could well have been paying Charan Singh back, quite unknowingly, for having been the biggest help in their comeback.

LET us go back a little to that morning of October 1977 when Charan Singh got Mrs Gandhi arrested. The Home Minister, all of 75 years at that time, was seldom known to smile. Even old associates could not remember him smiling, except perhaps when he played a hand of cards with wife Gayatri Devi. But that particular morning, a big smile played on his lips as he sat in the glare of arc lights and flashing cameras. He looked triumphant. “My CBI is very efficient,” he told the press happily. “Any country can be proud of such an organisation.” The Home Minister thought he had left no loopholes. He had done his homework well. In Uttar Pradesh he had the reputation of being an ‘able administrator’. Bureaucrats there were said to have been in awe of him. But at this point, some people had their doubts. “What if you fail?” one veteran journalist, known to be close to the Congress, had asked the Home Minister. “What if the charges against her don’t hold?” Charan Singh had looked at him contemptuously, as though he were a dirty insect.

“Will you resign if the charges fail?” another journalist had asked. “Why should I resign?” Charan Singh had retorted.

Overnight, Indira Gandhi had become a national martyr. “Even mummy herself couldn’t have written a better script for herself,” a jubilant Rajiv Gandhi, the Avro pilot, had told a foreign correspondent that evening. It had almost seemed as though Charan Singh had just followed the dictates of Indira Gandhi. “Political prisoners,” commented Le Monde, “are often regarded as martyrs in India, where prison, as was once the case for the majority of the members of Desai government, can be an antechamber of power.”

Charan Singh had played into her hands. The cronies of his own court had been telling him day after day that the Shah Commission (which probed the Emergency excesses of Mrs Gandhi, and which she kept defying valiantly as just ‘political vendetta’) was stealing the thunder that was his by right. Have her arrested, they said to him, and the country “will be at your feet. You will become the nation’s hero.”

Charan Singh had played into her hands. The cronies of his own court had been telling him day after day that the Shah Commission (which probed the Emergency excesses of Mrs Gandhi, and which she kept defying valiantly as just ‘political vendetta’) was stealing the thunder that was his by right. Have her arrested, they said to him, and the country “will be at your feet. You will become the nation’s hero.”

Instead, he became the nation’s laughing stock. Charan Singh had convinced Prime Minister Desai and some of his other colleagues that there were “foolproof criminal cases” and there was simply no chance for anything to go wrong. A more inept handling was hard to imagine. From beginning to end. A single action, meant to turn Charan Singh into a national hero, left the myth of his administrative ability thoroughly and completely exposed.

A few days later, Charan Singh got a letter from the party president, Chandra Shekhar, conveying his anguish over the mishandling of the arrest. The Home Minister smelt a personal censure, particularly because the letter had been endorsed by the party secretaries. He wrote out his resignation from the government. When his followers heard of it, they rushed to him. “If you resign, the Janata Government will collapse,” they argued. Chandra Shekhar, too, was persuaded to write another letter to Charan Singh, saying it had never been his intention to cast any aspersions on him. Charan Singh withdrew his resignation.

The version he gave to the press was different. “The political responsibility is mine. That is why I wanted to resign. According to the British tradition, I should have resigned. And my resignation is still written out. But my friends said if the British traditions are followed in other matters then I should resign, but if not, I should not resign. How long will the Janata Party last if you resign, my friends said…”

From an ‘untouchable’ of Indian politics, Charan Singh had turned Mrs Gandhi into a kingmaker. In less than a fortnight her fortunes changed beyond her wildest dreams. Until July 8, she had been in the trough of despair. She was almost certain that she would be prosecuted. Her erstwhile henchman, Devaraj Urs of Karnataka, had virtually driven her into a corner. At one go her party had not only lost Karnataka, but also the leadership of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha. That had seemed a blow from which it was hard for her to recover. And yet, she was suddenly holding the country’s political balance. Such a swift change it was that every politician, every party, was dazed. Even Devaraj Urs. All the calculations of this smart pipe-smoking politician had been based on two premises: that the Janata Government would somehow drag on for another year or so; and that Mrs G. would be in jail by October. Urs had gone wrong on both counts. On the contrary, he himself had receded into the shadows, almost as fast as he had got into the national focus. When Yashwant Rao Chavan decided to move a censure motion against Morarji Desai in the Lok Sabha, Urs had made a frantic telephone call to him asking him to stop it. “Please don’t upset all my plans,” he had told Chavan. Urs was already a little apprehensive about what might happen. Raj Narain had met him in Bangalore and Urs had got an inkling of what Narain could be up to. Was he thinking of joining hands with Sanjay Gandhi to upset the Janata applecart? That surely would upset all his plans, he thought. But in any case, it seemed too late; events were moving fast; they had taken a life of their own.

After Morarji’s resignation, President Sanjeeva Reddy had invited YB Chavan, the 66-year-old leader from Satara, to try his hand at forming a government. Had it been some days earlier, the President’s invitation would certainly have gone to Indira Gandhi’s trusted lieutenant, CM Stephen, but Urs had deprived him of that opportunity. Stephen had suddenly ceased to be the Opposition leader. Yashwantrao tried hard for a couple of days, and all the time that he was at it, Charan Singh was chafing in his lair, angry why Sanjeeva Reddy had to do this ‘useless exercise.’ It had indeed looked futile, but Chavan would not give up before the time given to him by the President: four days. Charan Singh’s men were warning that if the stalemate continued for too long there could be re-defections from the Janata (S) to the Janata. The leftist leaders started urging Chavan to give up. Finally, on July 22, Chavan went to Reddy and told him he had failed in his effort. Even so, he refused to write a letter to the President saying that Charan Singh should be called to form an alternative government.

IN the meantime, Madhu Limaye had put together a new political combine: the Janata(S), the Congress, the CFD group led by HN Bahuguna, Socialists and George Fernandes. He also claimed the support of the left combine and some regional parties. But it turned out that even this alliance could not reach the 270 mark required to form a government. Charan Singh then began talking to Congress (I). This time, Sanjay Gandhi told him that he would have to formally approach them, and so Raj Narain and some of his friends went to see Kamalapati Tripathi and C.M. Stephen. They told Narain that apart from other things, Charan Singh would also have to write a personal letter to Mrs Indira Gandhi. This meant trouble for the Charan Singh group. The left parties did not like this ‘formal surrender’ to Mrs G. The Janata Party had also activated itself. After prolonged negotiations, Morarji and Jagjivan Ram agreed that Desai would make the first attempt to form a new government. But within 24 hours, it was clear to Morarji Desai and Charan Singh that they could not form a government on their own. Neither could tot up 270.

Then suddenly came the startling announcement from Rashtrapati Bhawan: President Reddy had asked both Morarji Desai and Charan Singh to submit their lists of supporting MPs simultaneously. A full-blooded rat race resulted, with both sides trying all possible alliances. Morarji pleaded with Jagjivan Ram to mobilise his Harijan supporters within the Congress (I), in other words to buy them off. But Ram failed, giving Desai at least a sense of deja vu. He had maintained all along that even if Jagjivan Ram was made the Janata leader, he would not have been able to wean away a single Harijan MP from any other party. It was a tremendous discomfiture for Ram. His actual influence on Harijans stood exposed.

By July 25, the ‘rats’ gave up the race.

But just when Charan Singh had given up hope, he got a call from Rashtrapati Bhawan. Sanjeeva Reddy was himself on the telephone, informing Charan Singh that he had decided to invite him to form the government. “Could you see me in the morning?”

Could he see him! The 77 -year-old man could have gone running to him right then. It had been a big surprise. Just an hour earlier he had been telling his Jat mehfil. “This Sanjeeva will never invite me. He still remembers that I voted against him (in the presidential election which Reddy fought against VV Gin and lost) in 1969. He has not forgotten it…”

The tide had suddenly turned. He announced to his court: “My life’s ambition is fulfilled.”

The Congress (I) tirade began even before the Charan Singh government was installed. “Do you think we can tolerate a man who called Indiraji a liar?” Sanjay Gandhi had asked one of his cronies. “Just you wait and see what we will do to him. Make mincemeat out of the man.”

Within a couple of days everybody got a foretaste of things to come. Indira Gandhi lost no time in giving support to the crumbling ministry of Ram Sunder Das in Bihar, which was a signal to Charan Singh that he better behave. Sanjay had already told Raj Narain that as a first step toward retaining the support of the Congress (I), the Government would have to withdraw the notification under the Special Courts Act filed in the Supreme Court on July 19. They would not only have to withdraw the Kissa Kursi Ka case, but also remove Ram Jethmalani from the post of special counsel in the case immediately.

But having achieved his life’s ambition, Charan Singh’s natural self reasserted itself. He began showing his Jat guts. He announced the appointment of HR Khanna as the Law Minister, which amounted to showing a red rag to a bull. Khanna himself resigned a few days later, but even his successor, SN Kacker, promptly came out with a defiant statement: No withdrawal of Special Courts, no withdrawal of the KKK case.

Charan Singh seemed to be in a state of beatific bliss. It was almost as though he didn’t know what was happening around him, and if he knew he did not seem to bother. He thought now that he had reached his ultimate goal, it was a state forever. Nobody else, however, gave him more than a few months at the outside. Not even the newly sworn ministers. So utterly lacking in confidence were they that many of them would not even move to the bigger houses meant for ministers, which is considered the most attractive part of a minister’s post. “What’s the point,” one of the ministers told his friend. “It will be worse getting out of it after a month or two.”

So fragile was the government that many a foreign diplomat based in Delhi was in a quandary. One of them had asked me, rather hesitantly: “Do you think it would be impolitic to send our greetings to the new government at this stage?” It was only after both President Carter and President Brezhnev had sent their good wishes to the new government that most of the Delhi-based diplomats followed suit.

The trump card, everyone knew, was with the lady at 12 Wellingdon Crescent, or more precisely, with her son, who had taken charge of political manoeuvres long back. Nobody could say for sure how Sanjay Gandhi would play the card. The courtiers of the Gandhis only made the confusion worse confounded. Some said she would let Charan Singh go on till November, others said she would pull it down the very day the Lok Sabha opened — August 20.

UNTIl that time Ram enjoyed only a marginal support of the Harijans, but Mrs G. and her men were not at all sure that the situation would remain the same if Jagjivan Ram became the Prime Minister. What if he consolidated the Harijan votes in the country? And in any case, his political savvy was much greater than Charan Singh’s. And so it had to be Charan Singh. What led to the withdrawal of support so soon was his refusal to bail out Sanjay Gandhi from his immediate legal problems. A couple of days before Singh was to seek a vote of confidence in the Lok Sabha, Sanjay warned Raj Narain that if he wanted the government to continue, he must get his demands accepted. The two had met at their usual rendezvous — the guest house of Mohan Meakin. Their cover was a religious ceremony. Raj Narain had rushed back to Charan Singh and explained the situation to him. Charan Singh called his Law Minister, SN Kacker, and asked him to see if something could be done about the Kissa Kursi Ka case. After consultations with legal experts, Kacker gave a note to Prime Minister Charan Singh. The bottomline was: The withdrawal of the KKK notification at this stage would expose us to ridicule.

Charan Singh’s state of mind at that point is best reflected in the diary jottings of Kamal Nath, a close friend of Sanjay Gandhi who was also close to Charan Singh. Kamal Nath had a long conversation with Prime Minister Charan Singh on August 8:

Kamal Nath: I do not know how the present problem between Congress (I) and yourself can be resolved. The issues are being enlarged day by day and I feel…

Charan Singh: What are the issues? Indiraji’s offer for support was unconditional and now I am told this is to be done and that is to be done.

KN: There appears to be a big gap between what was said prior to your becoming the Prime Minister and what you are saying now.

CS: I do not understand all this. I have spent more than 50 years in public life and have far more experience than you. You must know what has happened since 1966 — the period when both you and Sanjay were young boys. Every understanding arrived at between me and Indiraji was broken by her. When I became the chief minister, she toppled me…She created a situation whereby I had to leave the Congress and form my own party…She has all along done everything to finish me. Now there are suggestions to me that I should write and thank her and also go and meet her. This is impossible. I will only meet her at some social function like birthday, for example. Otherwise I will not. Did Indiraji ever write and thank me for all what I did for her between 1966 and ’69? Did she ever come to me to thank me? If she has not, why should I?

KN: I think you are making this an emotional issue…I am sure there must have been a communication gap. I believe the problem can be…

CS: No. I do not agree. If Indiraji wants to support me there can be no bargain. How can I withdraw the Special Courts? When I die, I do not want people to say that Chaudhary Charan Singh became Prime Minister because he made a bargain with Indiraji and withdrew the Special Courts. Politically and publicly this is a wrong thing to do…

KN: Nobody has asked you to withdraw the Special Courts. They will be struck down by the High Court itself…The question is whether in your heart you want to do anything or not. If you really want to do something, but are finding difficulties, it is a separate thing; but the question is whether you want to or not.

CS: I am not even willing to say that I would like to help. There can be no promises from me. I am not willing to even express my intentions to help in any matter. Indiraji has no choice but to support me and if she has to support me out of necessity, where is the question of my promising anything? I do not see how she can support Jagjivan Ram…Let me make one thing clear — I am not afraid of a mid-term poll and convey this to Indiraji that Chaudhary Charan Singh is not afraid of facing the elections even if very few people of his party are elected. Doesn’t Indiraji realize that most of the MPs do not want a mid-term poll? Doesn’t she know that her own MPs do not want an election now? Voting against me will mean a mid-term poll.

KN: …Something has to be done by you to publicly show that you want our support. the spirit of coalition has to be evident to everyone.

CS: What can I do? Like what?

KN: I do not know, but personally I would have thought of some methods. Now it may be too late. We have agreed and stated that we do not want to participate in the ministry; but that does not mean that our suggestions regarding certain critical appointments should be rejected — for instance, the Attorney General could have been a nominee of ours; but he has been already appointed.

CS: The new Attorney General is your man. This is on record. He assisted Indiraji in the Shah Commission. In fact, this was pointed out to me by various people before his appointment, yet I appointed him….No. I am not willing to have any conditions. Indiraji has to support me of her own accord. I do not want to make any bargains. It is against my grain. I have a public image which I have to maintain…”

Did Charan Singh sacrifice his crown at the altar of his public image or was he really convinced that Indira Gandhi had no choice but to go on supporting him?

He was obviously taking a gamble, but in doing so he seemed to forget that Mrs G. herself was a great political gambler.

Excerpted from Prime Ministers: Nehru to Vajpayee by Janardan Thakur, Eeshwar Prakashan, New Delhi